A Proposed Policy Framework for Synthetic Media

None of the harms done (or possible) through synthetic media are unique to the methods of producing that media, and none of them can be prevented strictly through control of the technology of its production. Thus, a policy framework for addressing the risks of harmful synthetic media must be a policy framework for digital media writ large. While we have seen several policy proposals in recent weeks, most of them have been narrowly focused, with potentially huge unintended consequences. This draft is intended to highlight a few missing pieces, and to spark further conversation.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

The Audience for this Proposal

The harms of synthetic media are global in both source and target, and the stakes could not be higher. But the legislative landscape, as well as the landscape of public opinion, is hardly uniform. We have endeavored to envision a policy that could be adapted to, and adopted by, national and regional governments in North America, Europe, and India at the very least. (Many such governments are passing relevant regulations as we speak.)

Goals of this Framework

The goals of this framework are not to eliminate the creation of deepfakes (or any other form of synthetic media). They are:

To reduce the scope of harms, and…

To make authorship explicit, allowing us…

To push the underlying harms back into the jurisdiction of existing regulations…

…and to achieve all of the above with the utmost SPEED.

To be specific, there are real harms both in suppressing media suspected of being synthetic when it is not, and in allowing synthetic media to masquerade as actual. This proposal strives, not only to balance those harms, but to defer final judgment of such balance to the judiciary function in the appropriate jurisdiction as swiftly as possible.

It is additionally our goal not to propose any policy which would challenge or shift current regulation around freedom of speech, political expression or foreign interference.

What Media Would Be Covered Under This Policy?

While it is conceivable that synthetic media will be put to every possible (good and evil) use, the specific harms that have already been observed are the following:

Domestic Political Interference

Identity Theft & Fraud

Non-consensual Pornography

Foreign Political Interference

Military Disinformation Campaigns

Insurance Fraud

False Evidence

Any media (photographs, video, audio recordings, whether publicly broadcast or privately circulated) that attempts or achieves these harms, is within the scope of this policy.

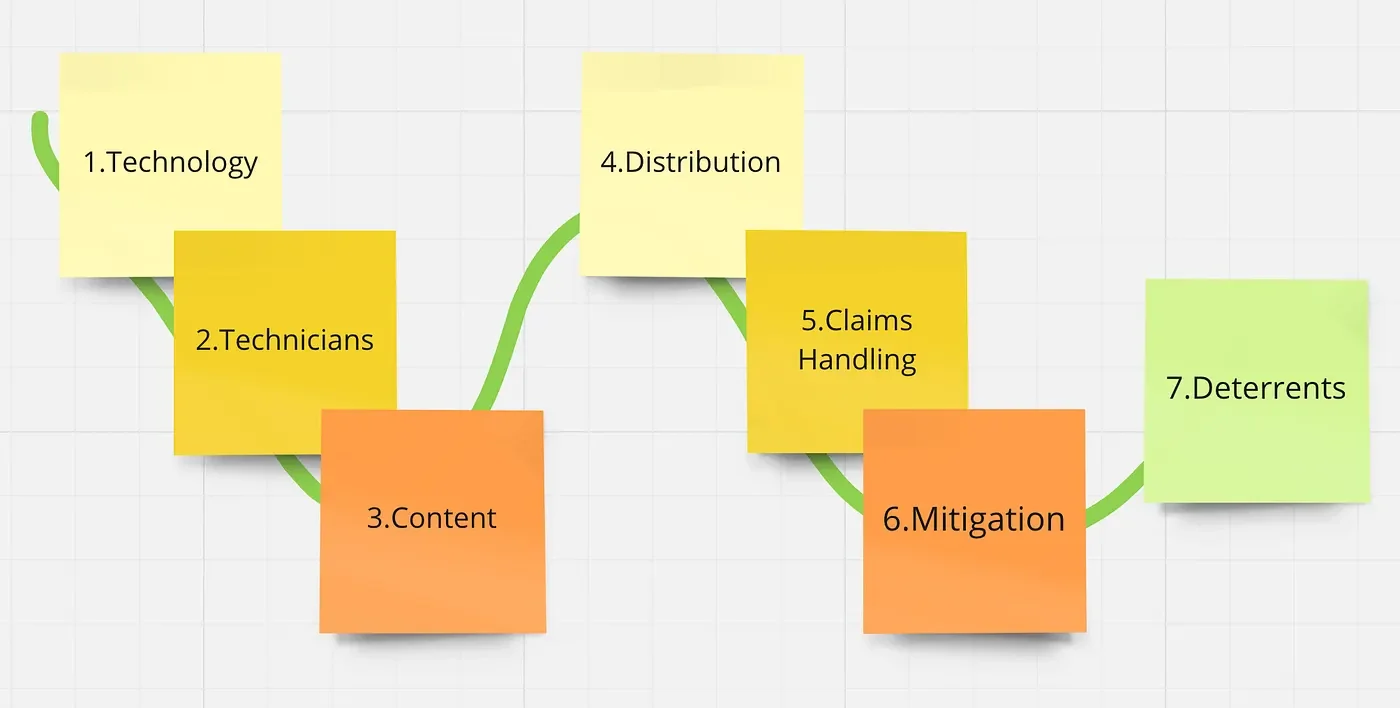

Framework for Media Policy

This framework must be shaped around the complete lifecycle of media, from capture or creation through publication to reporting and mitigation, and address the various actors involved.

A framework for media policy

1. Technology of synthetic media creation

We could try and regulate the use of “strong” deepfake approaches in the same way we regulate strong encryption (as a munition, and covered by ITAR); however, it is likely too little, too late for this approach. Today’s deepfakes technologies are already the AR-15 of synthetic media generation, and there is no natural technology “line” (resolution, frame-rate, amount of computing power per pixel or frame, complexity of training data set, etc.) that has not already been crossed…

… the cat is already out of the bag.

Instead, we must establish standards for media provenance, and require media that causes harm to defend its provenance. This mirrors policy that has been applied to the questions of copyright under the DMCA/ISD — once a claim of copyright infringement is made, the publisher of the media is obligated to provide evidence of their right to use the infringing media. When they have done so, the burden of proof shifts to the claimant to discredit those rights.

The minimum provenance for media must establish when, where, and with what device the original source media was captured. Constructed media that is not an edit of some original source media does not require provenance, but must not claim to be anything but synthetic.

(We acknowledge that tooling for capture and authentication of media provenance is not yet widely available; in the short term, the simplest form of provenance is a sworn affidavit of the media producer.)

2. Duties of Technicians

While one of the biggest threats of today’s media landscape is the growing ease with which amateurs, using small budgets and open source or freely available tooling, can produce compelling and confusing synthetic media, crafting truly undetectable deepfakes is (and will likely remain) the domain of experts, at least for now.

Obviously, criminals and foreign agents have no interest in, or requirement for, licenses or certifications. But the majority of professionals who develop deepfakes for legitimate purposes (movies, advertising, comedy) could be expected to subscribe to a standard of business conduct, attached to an oversight body. (This would be similar to how tradespersons, doctors, lobbyists, accountants and other professionals are governed). Any involvement in harmful media would put their ability to participate in lucrative, legitimate synthetic media at risk.

There has been no successful attempt to create a supervisory body for software professionals yet — if such a licensing or certification scheme is attempted in the context of AI, it would make sense to include media synthesis in its scope. Required certifications should be aligned with the size and scope of the company involved, similar to the difference between a “handyman” and a Red Seal carpenter.

3. Content Policies

We have a single, basic policy recommendation at the content level: Any media that generates a synthetic representation of a real person or contemporary event, must be labeled as synthetic.

Establishing such a labeling policy (and working closely with the major distribution platforms on the user experience of such labeling) will avoid most of the potential overreach of this policy framework, and preserve the rights to use synthetic media of all forms for satire and political commentary. The DEEPFAKES Accountability Act is a reasonable starting point for such labeling, and could be expanded with more depth on metadata storage and verification.

We believe such labeling must be within the media itself, and not just within the distribution platform. This will help to address the uneven regulatory landscape of distribution (what we have called the TikTok Challenge), as well as the major role that private, walled-garden communication groups now play in the circulation of misinformation (the WhatsApp Gap).

Of course, many of the harms of such content are not mitigated by simply labeling it — but we believe all of those other harms have existing regulations that address them. Beyond labeling, what is required is an expedited, low-friction mechanism for enabling and supporting those existing law enforcement efforts. This could include updates to Section 230 that would apply “duty of care” for unlawful content, such as has been suggested in Congressional testimony.

The second category of harmful media is media that has been substantially edited, such that the meaning and content of the original media is altered or obscured. Yet most media is edited before publication. In order to treat the content of “trivially edited” media as equal to the original source, we must agree on the definition of “substantially edited”, which might include changes to frame-rate, obscuring or inserting context, or selectively removing frames of video or audio. Substantially-edited media should have the same labeling requirements as synthetic media.

4. Distribution of synthetic media

It is likely impossible for any major media distribution platform to implement an objective, non-partisan content review process. (Certainly it is unlikely to happen under voluntary self-governance.) Even if it were possible, it will remain impossible to audit or confirm externally, and is therefore impossible to trust.

Fortunately, content review is not required. (As Linus Torvalds famously said, “With enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.”) What is required is a robust obligation to participate in extended reporting and mitigation programs (such as the existing UK Digital Services Act, etc). These mitigation programs will require platforms to support verification of emerging media provenance standards, and of publisher identity (already a common feature).

Specific policies for reporting and mitigation must include deadlines in hours or days, not weeks or months.

5. Handling Claims of Harm

Much like the DCMA process, requests for mitigation of harmful media must be submitted by those with “standing”. This is most simply the individual or a member of the group harmed, or a legal proxy. Outside of harms where an existing government agency is actively involved (such as election interference or foreign disinformation campaigns), it is likely inappropriate for the government to play a major role in monitoring and reporting content.

When a claim of harm is submitted (either to law enforcement, or directly to a media distribution platform), the claim receiver must contact the media publisher with a “demand for provenance”. Depending on the severity of the harms being claimed, the bar for establishing provenance could vary from a publisher’s affidavit, to authenticated metadata or chain-of-custody. It is important that the bar is based only on the stakes of the claim, not of the claimant or the publisher.

As long as the media publisher can provide provenance meeting this initial bar, their media remains available and unaltered; the burden of proof is now on the claimant to demonstrate that their provenance is false or insufficient (and the bar to prove false provenance must be much higher than that presented to the publisher). If it happens that the claimant can meet such a bar (or if the media publisher fails to provide provenance in the first place), the harmful media must be mitigated by the platform.

The timelines for notice and response must be proportional to the rate that the media is being viewed; in cases where harmful synthetic media is trending across social media platforms and being viewed by millions of people hourly, provenance must be demonstrated or asserted within hours. And in cases where claims of harm are extremely likely (such as political advertisements, media depicting famous persons, political figures, events in war, or pornography), the platform might choose to require provenance for initial media publishing.

Media platforms should maintain resources available for addressing and handling claims in proportion to the rate of claims within that region, topic, or community.

6. Mitigation of Harmful Media

As is well documented elsewhere, removal of false media is often the wrong approach. In the case of public access to edited content such as a deepfake, platforms have an obligation to redirect viewers to the unedited original content, describing but not displaying the harmful edits. Synthetic media that is intended as commentary or satire should have the option of applying appropriate labeling as a simple remedy.

For harmful media that was constructed entirely without an original source, where the publisher is unwilling to comply with labeling or where the media is unlawful regardless of labeling, the media should be replaced with an alternative media provided by the claimant.

Mitigation should emphasize redirection, not removal

Media platforms often have methods to notify viewers of new or updated content; they should use these methods to notify viewers who were exposed to the original harmful media of its synthetic nature, and provide access to the redirected or replacement content if relevant. Similarly, private communication platforms such as WhatsApp, Instagram Group Chats, etc. should send an additional message to chat group members (or previous members) with notification.

We should treat any mitigation of harmful media as essentially the enforcement of a court injunction, with the same responsibility to avoid passing judgment on the author or publisher before a final determination is made.

Media, especially sensational media, spreads rapidly. This spread is across many platforms, with clips of popular videos being copied from Youtube to Instagram to TikTok to Facebook. Media platforms have an obligation to coordinate mitigation efforts, such that claimants don’t bear the burden of chasing down harmful media across dozens of platforms. There may be regulatory amendments required to simplify such coordination.

7. Deterrents

The larger harms we are discussing (Foreign interference in elections, Libel, Non-consensual pornography, Fraud) are all serious crimes in their own right; additional deterrents for the use of deepfakes in committing these crimes would likely be irrelevant. What remains, therefore, is the tricky question of “unlabelled political commentary” — or misinformation campaigns masquerading as satire. Making the technicians, consultants and media creatives jointly responsible for the misuse of synthesis technologies is likely the most effective deterrent. Penalties for repeat offenders should be magnified.

Conclusions

While the threats posed by deepfakes may feel new and emergent, the underlying problem of synthetic media has been accelerating for decades. An attempt to address the harms of such media is long overdue. This framework is a draft, intended to address some gaps and spur further discussion.